All we have of her

On La Malinche, Choices, and What Remains of Us

Her name became an insult.

Her existence, a betrayal.

La Malinche.

The traitor.

This time last week, I didn’t know her name.

As I prepare to return to school full time, I’ve spent the summer enrolled in a theological Spanish intensive through Harvard Divinity School. After a summer steeped in Spanish grammar and translation that has transformed me in ways no language class has before, finals stress was starting to kick in for the first time in over a decade.

For our final assignment, my classmates and I will each select a Spanish text, anything from Bad Bunny lyrics to the writings of Teresa of Ávila, to bring into English. Knowing a bit about me (my passion for womanist theology, snake symbolism, and semantics), my professor sent over a few ideas. She suggested La Llorona, Quetzalcoatl, and added:

“I also wonder if you might be interested in some stories of La Malinche.”

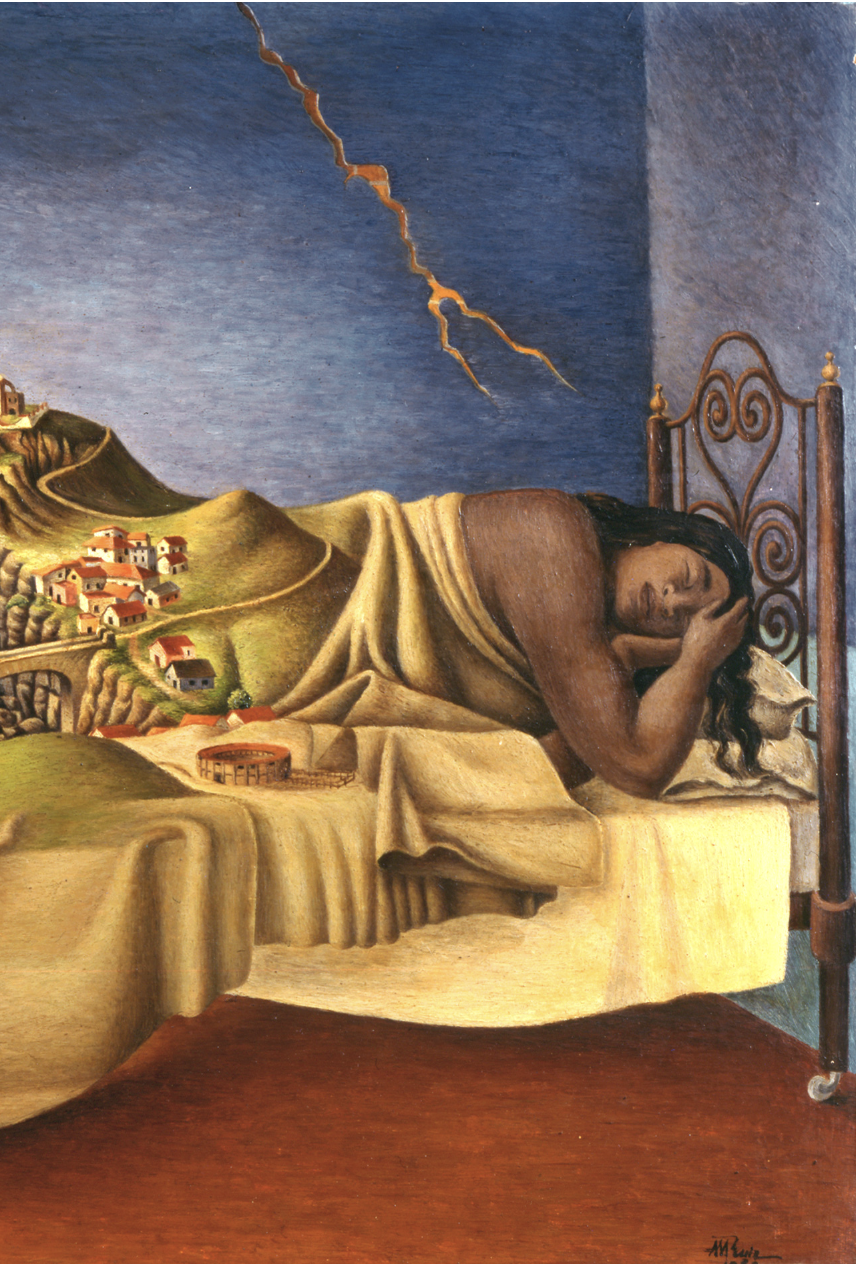

A woman known by many names, Malinche was born on the Gulf Coast of Mexico at the turn of the 16th century. Despite being born into a noble Nahua family (a large Indigenous people native to Mexico), Malinche was sold into slavery sometime between the ages of 8 and 12. After being traded multiple times, she was eventually offered as tribute to Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conquistador who would lead the invasion of Mexico…with Malinche at his side.

Translator.

Advisor.

Mistress.

Many historians agree: Cortés could not have conquered so much of Mexico without her. Fluent in Nahuatl (the language of the Nahua people), Mayan, and eventually Spanish, Malinche negotiated on his behalf, interpreted treaties, and advised his military strategy. And for helping the Spanish win, she was named la traidora. The traitor. The woman who helped destroy her own people.

And then her son was born. A Cortés.

Far from the first to give birth to a mestizo child (a person of mixed Indigenous and Spanish heritage, which is now the majority identity in Mexico), Malinche still became a symbol. Her name and her memory have come to represent the birth of colonized Mexico. She has been called both the mother of the mestizaje and the original betrayer of her people.

When my professor suggested I look into her story, I did a deep dive. I read articles, added books to my to-be-read list, listened to poems and podcasts, and even found a new musical theater production inspired by her tale. In a 2019 episode of the What’sHerName podcast, host Katie Nelson poignantly said:

“She left us none of her own writing. So all we have are the choices she made. All we can see are her actions.”

We have firsthand accounts of La Malinche from Spanish conquistadors and Indigenous writers alike, as well as centuries of texts inspired by her life. But if she ever tried to tell her story in her own voice, there is no record of it. As an enslaved Indigenous woman in the 16th century, it’s likely she was never taught to write. Whether her personal silence was a choice or a result of her social reality, when it comes to La Malinche - her perspective and intentions - all we can do is wonder.

I think about her being sold into sex slavery as a little girl; a decision historians believe was made by her mother and stepfather after her father’s death, likely to protect the inheritance of their future children. I think about the horrors she must have been forced to endure…a little girl with a knack for language and a longing to be loved.

I imagine how she must have looked at the world around her. Did she long for revenge against the family that tossed her aside? Did she begrudge a society that failed to see her humanity?

Discarded.

Overlooked.

Abused.

Did she pray for some kind of salvation? For someone to see her for all she was?

Noble.

Beautiful.

Brilliant.

When the Spanish arrived with gunpowder and other unknown wonders, did she think they were gods, as others did? Did she believe, even for a moment, that this was the deliverance she’d prayed for?

Like other modern thinkers who reimagine her story, I can lose myself in historical fan fiction, thinking of all the versions of her life that might have been.

But whether she saw Cortés as god or master, what difference does it make?

What position was she in to disobey? What would an enslaved teenager say to the conquistador and his armed battalions to change the course of history? What coup could she have led against her master without sacrificing herself for the very people who sold her into slavery in the first place?

I have come to understand privilege, most simply, as having at least one good choice to choose from.

I think of the single mother who leaves her child unattended because she can’t afford childcare for her job interview.

I think of Lilith under the coercive thumb of a man she did not choose in the Garden of Eden.

I think of La Malinche, a teenager who had already survived a decade of sex slavery when she was given to a man who would treat her like royalty in exchange for her strategic and linguistic support.

I ride for the vilified women of the world. My heart bleeds for these women who are made to choose between one gut-wrenchingly awful choice and another only to have their stories stripped of texture and nuance.

So my instinct is not to see La Malinche as a traitor, but as a survivor.

Not to blame her, but to protect her.

But our world has no compassion for a woman with no good choices.

Especially when she is not permitted to explain herself.

Even more so when she simply chooses not to.

“She left us none of her own writing. So all we have are the choices she made.”

I’ve thought about this line all week. What would historians claim to know about me if my choices, my actions, were all they had of me?

If you tell the story of the things I have done to survive without naming what it is I have survived, I become the villain. Sometimes I catch myself telling my own story that way, forgetting that I, too, was once a woman without a good choice to make.

At the feet of La Malinche, I resolve to be more intentional about what of me I leave behind. I will tell my own story, in my own voice.

And still - stories are silenced, journals get tossed, posts disappear, and books get banned.

I pray my actions don’t have to speak for themselves. I hope my writing can always accompany them without a character limit. But in case my words vanish, I want to move in ways that honor my values, and reflect my spirit. If my choices are all that remain, let me leave no doubt about who I was.

But Chingada I was not.

Not tricked, not screwed, not traitor.

For I was not traitor to myself…

Excerpt from "La Malinche" by Carmen Tafolla

Fresh filth dropping every other Sunday @ 10am PT👅🙏🏽

I’m so grateful for you!